Satire, “the use of humour, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticize people’s stupidity or vices, particularly in the context of contemporary politics and other topical issues.”

Satire has been used throughout history to express opinions and its significance is vast in providing context for many controversies and important moments in society.

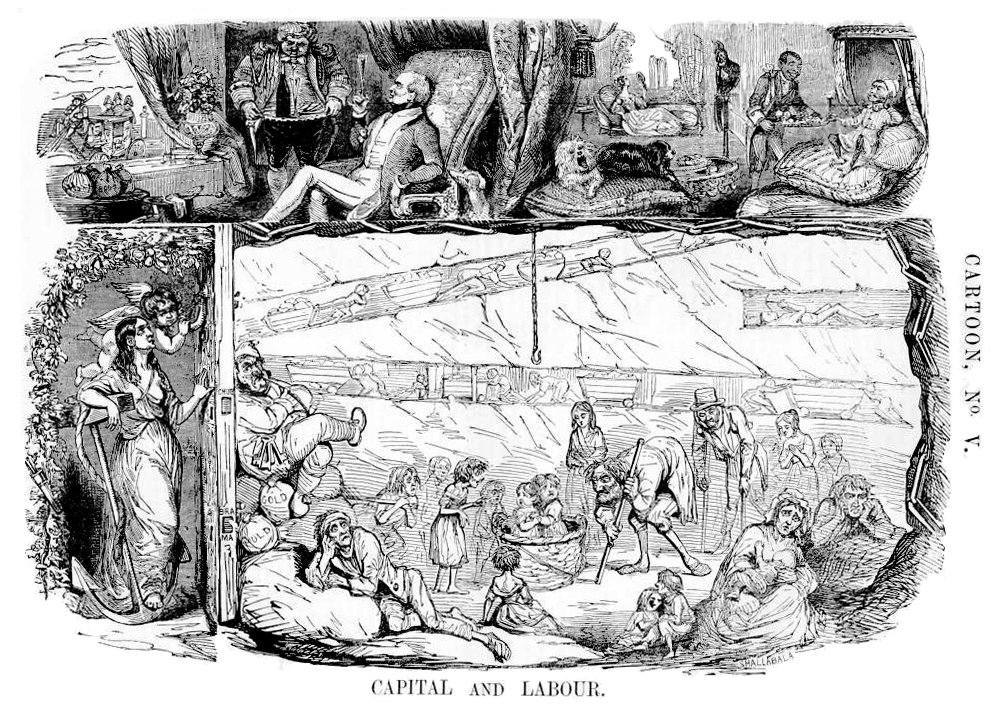

The Punch Magazine was one such outlet that cast a satirical eye on life in Britain from 1841-2002, it chartered the interests, concerns and frustrations of the country and today it stands as an invaluable resource for social historians. In its beginnings, it combined humour, illustration and political debate with a radical audacity, and in its first few years of existence, the magazine developed a reputation as “a defender of the oppressed and a radical scourge of all authority.” During the late 1800s, it reflected the conservative views of the growing middle classes and copies even spread as wide as royalty. In the Western world its significance on satire was wide reaching and it helped to revolutionise the world of illustration. The original idea stemmed from a man called Ebenezer Landells, a Parisian who took inspiration from Le Charivari and hoped to breach the gap and launch his own magazine over in London.

After Queen Victoria took the throne, the media world of London, which was full of scandals, blackmail and personal attacks was about to take a new direction, as Punch offered a more wholesome approach that the Victorians loved.

In the Early Years

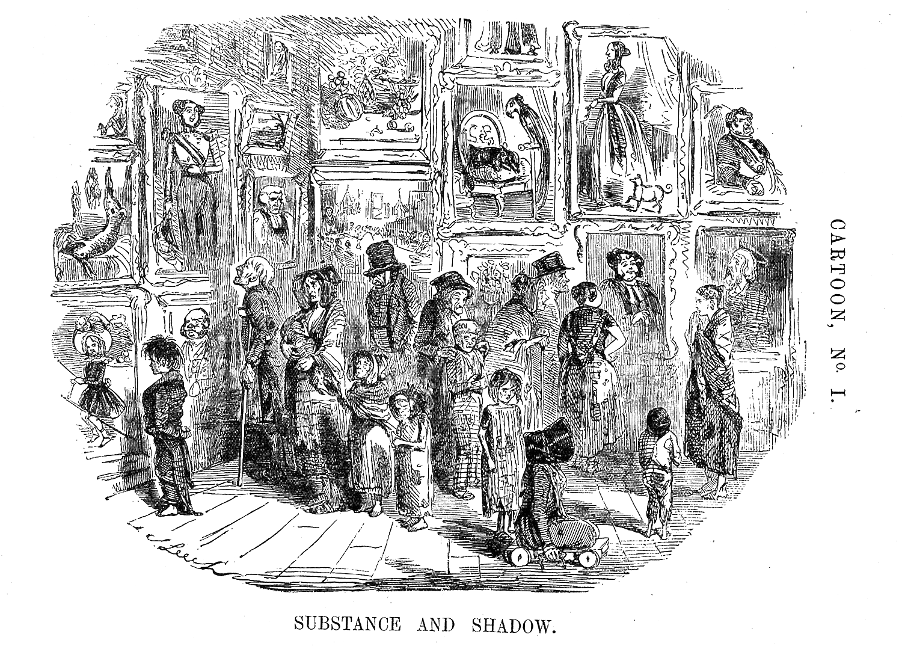

Punch in the beginning was more about politics than the pictures – whilst each issue featured a full-page satirical drawing that appeared at the centre of the magazine, called ‘Punch Pencillings’, it was only this drawing which had much significance. The prestige and importance of this illustration was passed around the various illustrators to express their take on current London life; with Kenny Meadows (1790-1874), Archibald Henning (1805-1864) and Henry George Hine (1811-1895) all making contributions. All three of these men were reliable draughtsmen, but their work was yet to make a significant and markable impact on the way the magazine was viewed, and society portrayed.

A development…

It wasn’t until the Punch Almanack in 1842 that it gained any large popularity or following, a key figure in this development was John Leech (1817-1864) who went on to revolutionise the magazine and what we now know today as a ‘cartoon’. He produced over 3000 drawings and his contribution to the magazine and to the world of satirical drawings has been second to none.

One particular illustration aimed at the ‘Palace of Westminster’ was a target of Leech’s criticism in 1843. The ‘Palace’ was a deemed a complete waste of public money, at the time London was a city of ill-health, poverty, slums and workhouses. The consensus was that an exhibition of competing rough designs for Westminster was a pompous and misplaced concern when much more pressing issues needed to be dealt with. The exhibition had been commissioned by politicians and Punch saw it simply as a means for the elite to celebrate their own importance. Leech’s finished piece of work is rather striking; it depicts a group of poor and ragged Londoners visiting the ‘Palace’. The clustered crowd sticks out like a sore thumb amongst the grandiose drawings, making it clear the misery that the poor find in work. Commonly, a finished preliminary sketch was known as a cartoon as from Frescoes (a painting done rapidly in watercolour on wet plaster on a wall or ceiling, so that the colours penetrate the plaster and become fixed as it dries). When Leech entitled this piece, “Cartoon No.1 – Substance and Shadow”, the use of the word ‘cartoon’ ridiculed the pretensions of the establishment and satirised their lavish attitudes. From that ‘Punch Pencilling’ onwards the illustration became known as a cartoon, and Leech therefore the first ‘cartoonist’.

Unlike media today in which the reader will often jump straight to the pictures for variety, an easier understanding – Leech made the reader aware of the illustrations and their importance was now on par with the writing. You could even go so far as saying it was the reason that people bought the magazine. If you mention the Punch magazine today, most likely people will recall the cartoons rather the significance of the writing.

Leech’s death

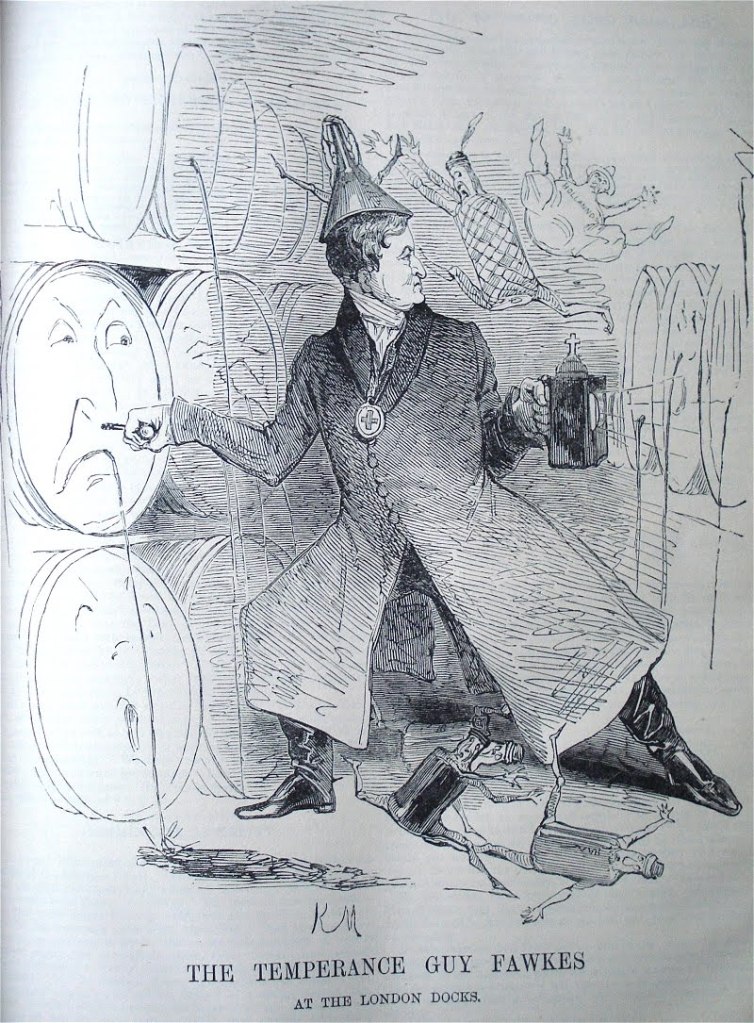

After Leech’s death the magazine was thrown into disarray, but Charles Keene helped to continue the legacy and his cartoons were arguably more polished and works of art in their own right. John Tenniel also had a casting impact, best known for his illustrations in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, he succeeded as the next main political cartoonist. However, there was much controversy surrounding Tenniel, his personal political standpoint was arguably portrayed through his work and and some of his cartoons upset radicals on the staff such as Douglas Jerrold. He denied showing political prejudice and claimed that “if I have my own little politics, I keep them to myself, and profess only those of the paper”.

A key example is argued by Lewis Perry Curtis, an American historian in the 1900’s, who pointed out that “despite their dignified quality, some of Tenniel’s cartoons partook of the dominant prejudices of the day. His depiction of Jews included such standard antisemitic features…”. However, his significance and impact cannot be side-lined even if his topics of attack were often questionable…

John Tenniel’s work

John Tenniel’s work

Leech, Keene and Punch revolutionised what we know as satire today as it became far more conventional. This is evident in this one such example, in which John Tenniel had been among those chosen for the Westminster frescoes that Leech had ridiculed just two decades earlier. Punch and cartoonists had reached a turning point, there were no longer interested in attacking The Establishment, it had become The Establishment.

So perhaps the balance had been tipped too far, but ultimately the progression is one that social historians can use as an invaluable resource for analysing the uprising of the British middle-class, and issues of the time – all encapsulated in one drawing.

In an article by the ‘Illustration Chronicles’, they say that to “study the magazine is to study the evolution of the cartoon itself. It chronicles the shift of satirical illustration from a reliance on caricature into an era of sophistication.” For me this brilliantly sums up the magazines importance in redefining and progressing satire today, and in continuing the evolution of the modern form of illustration.

Thanks for sharing the history of this magazine. I have to say I never wondered about its past, but now that I’ve read your post, I have a greater appreciation for it.

LikeLike

Aw thank you! Yes, there are so many older pieces of literature & art that need re-discovering. I guess the same stands for films! Finding and exploring great films even for today’s audiences.

LikeLike